From TATUL HAKOBYAN’s book ARMENIANs and TURKs

Minor skirmishes took place on the Kars front when the Armenian Corps commander General Nazarbekyan and his staff attended a special conference of Armenian political and military leaders in Alexandrapol on April 20 and 21, 1918. Among those present were members of the ARF Bureau, members of the military such as Movses Silikyan, Dro, RubenTer-Minasyan, and Andranik, and National Council delegates Avetis Aharonyan, Mikayel Papajanyan, Martiros Harutunyan, Nikol Aghbalyan, and Stepan Mamikonyan, and Western Armenian Defence Council delegate Vahan Papazyan, as well as Hovhannes Kajaznuni and Alexander Khatisyan, newly returned from Trebizond. There was even a Bolshevik, Poghos Makintsyan, present.

The Alexandrapol meeting was faced with the choice of accepting the Brest-Litovsk settlement together with the loss of Kars or of continuing the war. Kajaznuni described in detail the proceedings at Trebizond and implored the Armenian leaders to agree to the treaty. Former Duma and Ozakom member Papajanyan and several others concurred with Kajaznuni, but the overwhelming majority of the political and civic leaders, and all of the military representatives, rejected this stand and pledged an active defence against the brutal invader.

During the conference, the letters of Khachatur Karjikyan, the chairman of the Sejm’s ARF faction, were read, emphasising that the Armenian nation should not turn its back on Russia, for it is the only guarantor of the security of the Armenian nation and that Russia should not accept the idea of losing the Transcaucasus. At the time, almost all of Armenia’s political forces had a pro-Russia stance, despite refusing to accept the political and economic system of Soviet Russia. Historian Davit Ananun wrote that the Eastern Armenians greatly strove to hold on to Russia’s skirts, “but that skirt, despite the deep desire of the Armenians, escaped their grip.”

Kajaznuni presented the situation and tried to convince the participants that, given the situation, agreeing with the Azeris and Georgians and accepting the Brest-Litovsk peace conditions was the lesser of two evils, otherwise the fragile Transcaucasian Federation would collapse and the Armenian nation would be left facing the Ottoman Empire all alone. However, the general opinion was that they should refuse the conditions of the Turks and continue the war.

The prevailing disposition in Tiflis differed radically from the sabre-rattling atmosphere in Alexandrapol. The whole Georgian Menshevik party had been won over to the belief that it was imperative to renew negotiations immediately. The Turks had overrun the entire Batum oblast (region).

Akaki Chkhenkeli had foreseen the necessity of resuming talks and, after his return to Tiflis, he had continued to correspond with Vehib Pasha, who gave assurances that “friendly negotiations could begin as soon as the Transcaucasus desisted from its hostile ways and withdrew from the sanjaks [regions] of Kars, Ardahan, and Batum”.

The policy Chkhenkeli had advocated for weeks – a declaration of independence of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic–was finally adopted by the Sejm on the evening of the 22nd of April.

During that historic session, the ARF was confronted with two alternatives. By remaining loyal to national aspirations and its Russian orientation, it could reject the Muslim and Georgian decision to separate from Russia, thus committing the Armenians to continue the war alone. On the other hand, by yielding to the intractable reality of the day, it could comply with the Ottoman demand for an independent Transcaucasus beyond the Brest-Litovsk boundaries. The ARF decided in favour of declaring a separate Transcaucasian government.

Vratsyan describes it thus, “That day the Sejm hall resembled a cemetery. Armenians were not the only mourners. The Georgians were also not feeling good. The only happy ones were the Georgian nationalists and the Azeris in particular. Rasulzadeh was rejoicing. The Musavat faction felt like new bridegrooms. The Armenians were truly mourning. They did not feel like talking. Talk about what? Everything had been said. Kajaznuni put their feelings into words. Nervous, with disheveled hair, he climbed the rostrum and read, ‘Gentlemen, members of the Sejm. The Dashnaktsutyun faction, clearly realising the big responsibility it takes upon itself at this historical moment, joins in the announcement of an independent Transcaucasian state’.”

While still only premier-designate, Chkhenkeli assumed the functions of a legally authorised head of state. He communicated with Vehib Pasha and then commanded General Nazarbekyan to relinquish Kars without firing a shot. All his actions were kept secret from the ARF faction of the Sejm and even from those Armenian leaders whom he had approached to enter his cabinet.

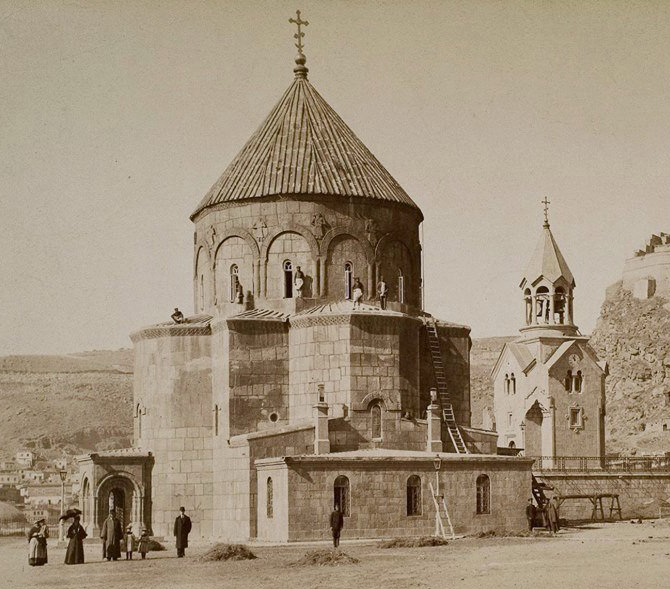

On the evening of April 25, the first Turkish units entered the city and, on the following day, General Deev, Military Commissar Misha Arzumanyan, and several other officials formally delivered the city to Colonel Kâzim Karabekir. The fall of Kars stunned the Armenian world. Refugees and irregular troops spilled into Yerevan province bringing anarchy, famine, and epidemic with them.

In Tiflis, the political atmosphere was lethal. Angry mobs of outraged Armenians rushed through the streets denouncing the Transcaucasian government. The most humiliated were Kajaznuni and Khatisyan, the two Armenian delegates to Trebizond who had considered themselves to be the close associates of Chkhenkeli and had already agreed to participate in his cabinet.

Thousands of Armenians were fleeing towards the province of Yerevan in panic. About twenty thousand people left Kars after burning the city’s best buildings. On April 25, the Third Ottoman Army entered the Armenian fortress city without a fight. However, contrary to agreement, the Turkish armies did not stop and the Armenian forces retreated fighting to Alexandrapol. On April 28, the Armenian army crossed to the left bank of the Akhuryan, blowing up the fortifications on the right bank.

Khatisyan wrote: “The sudden flow of the refugees to Armenia, the lack of food, the war, and the epidemic had created such severe conditions in the Armenian provinces that it was necessary to accelerate the signing of the peace treaty. The conference was to take place in Batum. We once again began forming a delegation, headed again by Chkhenkeli. Kajaznuni and I were the Armenian members. This time our mission seemed quite straightforward. We thought that we only had to go and sign a treaty with the Brest-Litovsk provisions.”

On April 26, the Sejm had endorsed the structure of the government, headed by Chkhenkeli. In Batum, it was Chkhenkeli who continued negotiations with the Turks that had been interrupted in Trebizond. His government was ready to accept all the points of Brest-Litovsk.

The Ottoman plenipotentiary, Halil (Kut) Bey responded by saying that the struggle between the Turkish and Transcaucasian forces had resumed, “Unfortunately blood was shed. Thus, the character of our relations has changed and I cannot allow that the Brest-Litovsk Treaty to be recognised as the exclusive basis for our negotiations”.

At the May 11 session, which proved to be the only official meeting, Chkhenkeli insisted that the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk be honoured. Halil Bey ridiculed Chkhenkeli’s claim that the Transcaucasian delegation at Trebizond had accepted the treaty and that it should thus serve as the basis for current talks. The Turkish chief delegate then warned that further obstinacy would result in disastrous consequences. Halil’s words were not empty threats. While the bickering in Batum increased, Turkish armies rolled through Alexandrapol towards the few remaining Armenian districts of the Transcaucasus. Turkish Armenia had already been obliterated. It was now the turn for Russian Armenia.

The Armenian delegation was left alone in Batum. Moreover, the Tatars defended the Turks. “When we demanded that the Turks leave us the Armenian parts of the province of Alexandrapol, the Tatars insisted that the village of Vagharshapat should be Armenia’s capital city and demanded that Yerevan should be annexed to Azerbaijan,” wrote Khatisyan. “NesibUsubbekov and Fathali Khan Khoyskii insisted that Yerevan is a Tatar city and that the Muslims would not forgive them if they conceded Yerevan to the Armenians.”

There was also no general stance amongst the leaders of the Ottoman Empire on the issue of Armenia’s independence.

Before the Batum conference, Talât had warned Halil Bey not to allow for a strong Armenian state. Accordingly, if no obstacles weremade for Armenians, Armenians across the whole globe, about five million in all, would migrate and establish an Armenian state. In fact, the central idea was to establish a weak Armenia and weak Georgia.

In the beginning of the Batum conference process, Mehmed H. Hajinski asked (Ismail) Enver Pasha about his ideas when it came to an independent Armenia. In his reply, Enver said that they did not oppose an independent Armenia if Armenians stopped engaging in the plots of Russia and Britain.

However, Enverhad a tough attitude towards Armenia. But Halil sent a telegraph on May 8, 1918 to Enver saying that Transcaucasia’s annexation would not be beneficial for the Ottomans. For Halil, establishment of a buffer state between Russia and the Ottoman State should instead be supported.

However, when the Turkish armies crossed the Akhurian River, Enver’s stance towards the Armenians grew even tougher.

In the instructions sent from Enver to Vehib on May 27, it was pointed out that an independent Armenia would have a high population with the migration of Armenians living abroad and in that case the Ottomans would face an even worse enemy compared to Russia, and therefore Armenian territory should be divided between Georgians and Azerbaijanis, so that the inhabitants of places like Yerevan, where the Muslim population was high, would be preferable instead. However, in his response, Vehib Pasha emphasised that they would not be able to completely eliminate the Armenians in this manner.

According to Talât Pasha, the Ottomans would establish Armenia as a small state during the peace agreement and would thus create an impression of peace regarding the Armenian problem. The ones who were supporting hawkish solutions, like Enver Pasha, thought that the liquidation of the Russian Armenians completely would be the best solution.

General von Lossow, the German representative at the Batum conference, also wrote that the Turks had undertaken the total liquidation of the Transcaucasian Armenians. Von Lossow stated the matter more precisely in the following weeks: “The aim of Turkish policy, as I have always maintained, is to take possession of the Armenian districts in order to extirpate the population living on them,” “Talât’s government wants to destroy all the Armenians, not only in Turkey but also outside it,” “After completely encircling the vestiges of the Armenian nation in the Transcaucasus, the Turks intend to starve the Armenian nation to death – that much is obvious.”

General Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, the former chief of military operations in the Ottoman War Ministry, who was appointed to head the German Imperial Delegation to the Caucasus in June 1918, was himself convinced that “the Turkish policy that consists in provoking a famine is evidence, were there any need for further proof, of the will to annihilation that the Turks harbour towards the Armenian element.”

This book covers almost the whole spectrum of Armenian-Turkish relations, including the different attitudes of Diasporan circles and masses to the past, present, and future relations with the Turks. Tatul Hakobyan’s work is a smooth mix of history and journalism. This extremely complex and significant period of history is presented coherently, simply, in an easy to follow narrative that links together the various periods during the tumultuous 100 years beginning in 1918. Armenians and Turks, is packed with political insight, historical revelation, and even a poetic vision of a complicated relationship which unfolded, over a century, between two peoples. Hakobyan has established himself as an indispensable journalist, expert, and scholar of this ongoing saga. Written in the journalistic style using strict standards of scholarship, the author has evidently undertaken wide-ranging research. This book is of great interest not only to historians, diplomats, or experts who study issues of Armenian-Turkish relations and their impact on the future of the South Caucasus, but also for a wide range of readers.

This book covers almost the whole spectrum of Armenian-Turkish relations, including the different attitudes of Diasporan circles and masses to the past, present, and future relations with the Turks. Tatul Hakobyan’s work is a smooth mix of history and journalism. This extremely complex and significant period of history is presented coherently, simply, in an easy to follow narrative that links together the various periods during the tumultuous 100 years beginning in 1918. Armenians and Turks, is packed with political insight, historical revelation, and even a poetic vision of a complicated relationship which unfolded, over a century, between two peoples. Hakobyan has established himself as an indispensable journalist, expert, and scholar of this ongoing saga. Written in the journalistic style using strict standards of scholarship, the author has evidently undertaken wide-ranging research. This book is of great interest not only to historians, diplomats, or experts who study issues of Armenian-Turkish relations and their impact on the future of the South Caucasus, but also for a wide range of readers.

Paperback: 440 pages,

Language: English, Second Revised Edition

2019, Yerevan, Lusakn,

ISBN 978-9939-0-0706-9.