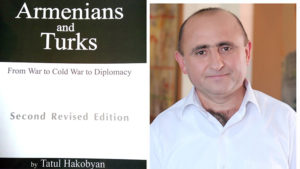

This chapter is from Tatul Hakobyan’s book- ARMENIANS and TURKS

During the months of October and November, 1918, the most discussed issue in the Ottoman parliament became that of holding those accused of involving the empire in World War I and organising the massacre of the Armenians accountable in court. On October 19, Prime Minister (Grand Vizier) Ahmed Izzet Pasha presented the government programme in parliament, which, however, did not include the issue of investigating the crimes committed during the war years. In response to criticisms, Ahmed Izzet announced, “We promise justice.”

There were intense discussions on the issue of the Armenian massacres during the parliament session of November 4. In the early morning of November 2, several key figures of the Committee of Union and Progress had secretly left, travelling along the Bosporus and Black Sea routes. This gave cause to those opposing the CUP, who had formerly lived in fear, to sound the alarm in the press and warn the government to arrest the other accomplices before they too could flee. The leader of Hürriyet ve İtilâf, Mustafa Sabri, declared in the Turkish daily Sabah that the Ittihadist criminals were able to escape thanks to Izzet Pasha.

The role of the Ottoman parliament was important in the process of bringing criminal actions against the Ittihadists. Giving in to pressure, the Fifth Parliamentary Commission, Beşinci Şube Tahkikat Komisyonu, was formed in parliament at the suggestion of the Arab parliamentary deputy from Divaniye, Fuad Bey. On the basis of the ten points in the motion by Fuad that had been adopted by the parliament, the Fifth Commission conducted hearings of the ministers of the war cabinets still living in the capital. The British and French intelligence services followed the commission’s work, carried on from November to December 1918, with great interest.

The Commission’s responsibility was to interrogate the ministers of Said Halim’s and Talât’s governments during the war and decide if they should be convicted as criminals or not. However, the committee could not summarise its conclusions and put it to a vote in parliament because on December 21, 1918, Sultan Mehmet VI Vahideddin dissolved it. Nevertheless, information and documents collected by the committee were subsequently of great help.

Genocidal crimes were committed against the Armenians following the passage and enactment of the Temporary Deportation Law (27 May, 1915) and the Law on Abandoned Property (26 September, 1915).The Temporary Deportation Law had two objectives: to commit genocide under the name of deportation and to create the legal basis in order to carry out the crime. The Temporary Deportation Law said in particular, “Suspecting spying or betrayal, based on special military laws, the commanders of the armies and separate forces and divisions can deport and resettle the residents of villages and towns, separately or en masse, to other localities.” That law should have been taken to the Ottoman parliament for ratification in September 1915, but it was not. The ridiculous thing is that, more than three years later, on November 4, 1918, this law was presented for ratification by parliament at the insistence of Armenian members of parliament, when the Armenians were exterminated and the Ottoman Empire defeated in war.

As French-Armenian historian Raymond Kévorkian points out, the Armenian deputies presented the law for ratification in order to point the government to its responsibilities. After Fuad’s motion was adopted, the deputy from Sis, Mattheos Nalbandian, together with five of his colleagues, filed a written request that the government state how it regarded the crimes committed after the passage and enactment of the Temporary Deportation Law and the Law on Abandoned Property. “Thus, they invested the terrain marked out by Fuad’s motion, a tactic that had the merit of placing their Turkish colleagues before their responsibilities, since it was with reference to these two laws that parliament should have voted that crimes had been committed,” writes Kévorkian.

During the months of November and December, the Armenian members of the Ottoman parliament actively participated in discussions on the Armenian massacres– what was the nature and scale of the crime, who were those responsible, and how could the damage and loss incurred be remedied. Sometimes the Greek members of parliament supported the Armenians, firstly and foremost, Emmanuel Emmanuelidi. Six Armenian members of parliament who participated in the discussions were Matteos Nalbandian (Kozan, or Sis), Onnik Ihsan (Izmir), Hovsep Madatian (Erzurum, or Karin), Artin Boshgezenian (Aleppo), Hakob Khrlakian (Marash), and Tigran Parsamian (Sebastia). Two Armenian members of parliament from Mush, Gegham Ter-Karapetian, who was ill and Vahan Papazian, who had left Turkey, and Petros Halajian from Constantinople did not participate. The other three–Grigor Zohrab, Vardges (Hovhannes Seringiulian), and Vramian (Onnik Derdzakian) – had been treacherously killed.

In a book dedicated to the annihilation of the Armenians, Ottoman parliament member Ahmed Refik writes in surprise that while the Armenians were being sent to Der-Zor and being massacred, the Armenian members of parliament in Constantinople maintained their warm friendly relations with Talât and the other Ittihadist leaders who had organised the annihilation of the Armenians.

During the November 4 discussions, the Armenian members of parliament condemned the crimes carried out against the Armenians, at times coaxingly, at times threateningly, and at times through ambiguous and hidden expressions. Internal Affairs Minister Fethi Bey (Okyar) was forced to personally appear in parliament to give explanations. Of course, the question arises as to why these same Armenian parliament members had remained silent throughout the genocide itself and had managed to avoid the massacres. On that day Emmanuelidi presented a resolution consisting of eight points, in which it said that one million Armenians, including women and children, had been killed, for no crime other than being Armenian. The killings and deportation of the hundred thousands of Greeks were also noted in the resolution.

During discussions on18 November, the Armenian MP Artin Boshgezenian, a Young Turk deputy from Aleppo whose previous interventions had been marked by extreme caution, decided to raise the question of the collective murder of his compatriots. In his long speech Boshgezenian described “the Armenian massacre” as “a major crime, one of the saddest, bloodiest pages of Ottoman history,” that the country as a whole was being held responsible.

Parliament member GeghamTer-Karapetian from Mush was the only Armenian MP in the last Ottoman parliament that had been elected exclusively by Armenian votes. The remaining Armenian MPs had entered parliament through the Ittihadists or with their help. Ter-Karapetian’s survival was accidental. He had not been deported, since he was ill in bed. However, the illness did not hinder him from attentively following the massacres of eighty to ninety thousand Armenians from the city of Mush and the villages surrounding the valley of Mush, one of the most horrifying and revolting scenes of the Armenian Genocide.

During the December 9 session, Armenian MP from Sivas and former member of the CUP, Tigran Parsamian, read the text of the deceased Ter-Karapetian’s speech: “How did it come about that the Armenian living in the western provinces, Karin, Sebastia, Kharberd, Van, Tigranakert, and in the town of Urfa, were deported, more than 1.5 million Armenians were dispersed, massacred, and killed? As a result of this general massacre, the furniture and real estate of the Armenians in that region, all valuable goods kept in the monasteries and churches, have been looted and the local clergymen killed and annihilated. A fraction of the children left alive from this awful violence have been dispersed here and there after being forced to convert.”

In photo- Talât

Ask this volume in the following Yerevan bookstores

Bookinist, ArtBridge, Zangak, Noyyan Tapan, Epigraph.