The winds of Gorbachev’s ‘perestroika’ and ‘glasnost’ blew through the provincial town of Hadrut (southern NK) at the end of 1985 and beginning of 1986. Artur Mkrtchyan returned from Yerevan that year and was appointed director of Hadrut’s museum. He would later become Nagorno Karabakh’s first elected president (speaker of parliament). Three months later he would be unjustly killed.

Nelly Kasparova speaks of injustice as if the struggle against all the world’s injustices were placed on her fragile shoulders. Daughter of Ashot Kasparov, a hero of the Soviet Union, she has devoted 30 years of her life to educating children. She is a Russian language teacher at Hadrut’s school and almost two decades ago was a member of the region’s young intellectuals group who would write letters about national issues to Gorbachev in the Kremlin.

Kasparova’s smile, which is as attractive as it is disillusioned, points to her impotence in her struggle against injustice. On a cold winter evening in February, 2008, sitting around a table in Hadrut, she and Gagik Avanesian remember the days when the people of the region fought for the reunification of Karabakh with Armenia by collecting signatures. At the mention of Arthur Mkrtchyan, Avanesian’s face expresses regret, while Kasparova’s bright smile immediately vanishes. She hides her head in her delicate hands and starts to weep.

The first petition began in Hadrut, probably because the leading figures of the Movement were originally from that region – economist Igor Muradyan, historian Artur Mkrtchyan, architect Manvel Sargsyan, painter Emil Abrahamyan. Soon after, they were joined by Grisha Hayrapetyan, Gagik Avanesyan, Nelly Kasparova and others. The local communist leaders were worried that their superiors in Baku would find out and sack them. Because of this, they pressured the activists of the Movement, but sometimes turning a blind eye.

In November 1985, Emil Abrahamyan suggested that 23 year old Gagik Avanesyan help with the petition drive. They wanted to install a satellite in Hadrut to be able to catch Armenian television. In the end, the satellite was never installed. In its place, a group of dedicated individuals had already “caught” the winds of ‘perestroika.’

Avanesyan recounts, “The process of petitioning for the installation of a satellite was very difficult. Only 250 signatures were gathered over several months. We spent days persuading people that there was nothing anti-Soviet or nationalistic about it. A year and half later, Igor Muradyan came to Hadrut. Manvel Sargsyan introduced me, Nelly, Emil, and the others to him. We had only heard about Igor. We knew that he had sued (former and future Azerbaijani leader) Heydar Alive for pursuing an anti-Armenian policy. So, we started another petition; this one for uniting Karabakh with Armenia. It was not that hard anymore. People were more readily persuaded since no one had been punished during the previous petition drive.”

During the conversation, which lasted 3-4 hours, Nelli said nothing of those heady days. However, the presence of this pretty woman and the enthusiasm of Gagik, transports one to the past, when the spirit of Hadrut’s youth was ablaze with patriotism and their heads were filled with the incurable idea of uniting Karabakh with Armenia.

The regional Khorhurdain Karabakh newspaper’s only coverage of the events taking place in Artsakh on February 21, 1988 consisted of printing the decision taken the day before by parliament of the NKAO during a special session on its front page. The 110 Armenian members of the parliament voted in favor, while the 30 Azerbaijani members didn’t take part in the session. The Armenian parliamentarians proposed transferring the NKAO from Azerbaijan’s structure to Armenia’s.

Baku tried to prevent the spread of the Karabakh movement. The Second Secretary of Azerbaijan’s Communist Party’s Central Committee, Vasili Konovalov, arrived in Stepanakert with other officials. Earlier, on the evening of February 11, the session of the regional committee’s bureau met and decided to have talks with the party activists and enterprise managers in the regional center and districts. The aim was to have these individuals condemn the events taking place in Nagorno Karabakh – the petition, the visit of delegations from Karabakh to Moscow, and the intention of uniting Karabakh with Armenia.

During a meeting with party activists on February 12, Vasili Konovalov, Karabakh party leader Boris Kevorkov and Stepanakert Mayor Zaven Movsisyan, condemned the Movement and the ‘extreme separatists’ supporting it. Movsisyan labeled events taking place in the region the handiwork of the extremists. Kevorkov warned that the separatists had no place in Karabakh. His message was clear – the region was and will remain an inviolable part of Azerbaijan. Konovalov announced that he knew the name of each and every extremist and separatist who had to be isolated from the rest of society.

However, the session of the party active did not progress in the way Baku had envisaged. The heads of Karabakh’s enterprises made speeches condemning Baku for decades of discriminatory policy toward Karabakh. Maxim Mirzoyan, one of the managers of the Stepanakert companies, condemned Kevorkov and the policy of Baku, whose objective was to ensure no Armenians were left in the region. Vladimir Sargsyan, director of the local college, supported Mirzoyan and in turn criticized the social and economic steps taken by party leaders. The director of the silk factory, Radik Atayan, like Mirzoyan, proposed to determine the status of Karabakh through a referendum.

By February 12, painter Emil Abrahamyan and his friends began to feel the breath of the people on their backs. Different officials had been dispatched to districts in Nagorno Karabakh to try and “extinguish” the people’s wrath.

“One of the NK leaders, Vladimir Osipov came to Hadrut,” recalls Mr. Abrahamyan. “The purpose of the party active was to put an end to the Movement and prepare a report that would prohibit activities taking place. We decided not to permit it, as it could have led to uncertainty among the people and processes could have gone in another direction. That day approximately one thousand people gathered; that was something unheard of in Hadrut.”

In 1987, before the delegations had left for Moscow, the group of young intellectuals in Hadrut had written to Gorbachev, stating that the only way to resolve the issues of the Armenians of Artsakh would be to reunite Nagorno Karabakh with Armenia. After this letter, the local authorities launched their tactics of repression.

“The young officials of Nagorno Karabakh made their choices easily. The more mature party officials were strongly allied with the authorities in Azerbaijan. Baku was a familiar city for them. Taking a position on national issues was harder for them and they could not even understand the essence of the issue. For example, on February 12, when Hadrut rebelled, Chief of Police Armen Isagulov arrived on the scene to instill the people with fear. The next day he called us in to understand what we wanted. I told him what we wanted. He said that we were crazy and it was impossible to realize such things. He could not understand us. Some of the Karabakh authorities of today were not with us at that time. I am not saying that they were against us in spirit, but politically they could not stand with us,” Abrahamyan recalls.

On February 12, the meetings of the party active in Stepanakert, Hadrut and other districts were disrupted. The rally which had begun in Hadrut moved to Stepanakert. The Movement had become unstoppable.

Of course, Baku was informed of the events underway in Nagorno Karabakh. Valery Atajanyan was one of the NK Armenian bureaucrats of Azerbaijan’s Central Communist Party. In January he had returned for a few days to his father’s home. “I had kept in touch with my brother, Maxim Mirzoyan. I was informed that operations had gone underground, I suggested giving them an official nature. But I wasn’t in favor of having Armenia pulled into the operations because that would take it to another level; the issue would be transformed into a disagreement between two republics. I proposed resolving, first of all, the issue of removing the Nagorno Karabakh from Azerbaijan’s structure.”

Valery’s brother, Vasily who was the director of Stepanakert’s shoe factory recalls, “As soon as Abel Aghanbegyan spoke about Karabakh in Paris and Gorbachev admitted in Yugoslavia that there were ‘white blemishes’ in Soviet history which were necessary to correct – this was a drop of water for a parched soil. When my brother came, we got together at Maxim Mirzoyan’s house. A discussion ensued that the petition didn’t have much value, that a session must be called because that corresponds to the Soviet constitution.”

At the end of February, Valery Atajanyan proposed the idea of convening a session to the activists of the Karabakh Movement. “The guys said that they were collecting signatures and sending delegations to Moscow. I said all of that was good, but in order to give these efforts a legal dimension, a decision by a session was the key document needed. To employ the ‘perestroika’ and ‘glasnost’ initiated by Gorbachev was within their rights and under that banner it would be very easy to convene a session and agree to a decision,” he says. After spending a few days in Stepanakert, Atajanyan left for a holiday in the Northern Caucasus and then returned to Baku.

Writer Vardan Hakobyan from Artsakh recalls that Vigen Hayrapetyan, a mid-level NK official, and Hrand Yepiskoposyan, a professor at Moscow’s State University, proposed convening a session for unification when the delegation of NK intellectuals left for Moscow at the beginning of February1988. This delegation would leave for Moscow with the intention of presenting their request to unify Nagorno Karabakh with Armenia.

“We returned from Moscow and what did we see? Artsakh had risen and the square was boiling over. Each item of news that we brought from Moscow to the square raised a new wave among the people, making them more resolute in their decision. Arkadi Manucharov had become the head of the movement in Artsakh, and he formed a group that initiated a move to hold a session.”

Kevorkov was aware of the events. The leaders of the Movement had even suggested that he join the nationwide struggle. During one of the meetings in mid-February, Kevorkov had made an appeal to put an end to the rallies and send people home. The regional and republican authorities had lost control of the situation in a very short time. During a session of the Party’s Politburo, Asadov, an official of Azerbaijan’s Central Committee warned that a hundred thousand Azerbaijanis were ready to invade and organize a massacre in Karabakh.

Soviet Azerbaijan’s leader Baghirov arrived in Stepanakert on February 20 with the aim of putting an end to the Karabakh Movement and disrupting the session. While Baghirov and the Armenian officials who had accompanied him were trying to convince the members of parliament to pull back from convening a session, the people gathered in the square were constantly chanting, “Session! Session!” The Azerbaijani leader left the hall dejected.

“The session took place on February 20. Two days later, inspectors of the Central Committee, mostly Armenian and Russian, were dispatched to Stepanakert on the same plane as Demichev and Konovalov. They intended to convene a meeting to oust Kevorkov. From the airplane window we saw that people had gathered near Askeran. Cars could be seen burning beside the beer factory. From that day on, I never returned to Baku,” Valery Atajanyan recalls, smiling.

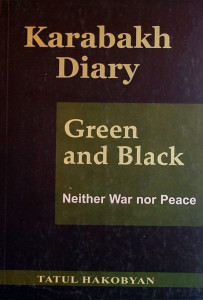

From Tatul Hakobyan’s book

An exceptional and informative work based on a rich and varied source base. Its impartiality is striking. A much needed monograph destined to persevere as the ‘textbook’ for Armenian diplomacy. As a pioneering initiative that presents an accurate reinterpretation of the Karabakh struggle for self-determination, this book captures the essence of the issue with an illuminating portrayal of many of the key figures and events that have come to define the Karabakh issue. The conflict cruelly shaped the destinies of thousands of average people and the ordeals they bore underline the responsibility of those at the top, in whose hands a resolution of the Karabakh conflict rests. The author’s secret, revealed in the pages of Green and Black, is that he does not shy away from presenting those facts and realties no longer considered expedient to remember. Anyone wishing to be informed and regarding the Karabakh conflict must read this book.

An exceptional and informative work based on a rich and varied source base. Its impartiality is striking. A much needed monograph destined to persevere as the ‘textbook’ for Armenian diplomacy. As a pioneering initiative that presents an accurate reinterpretation of the Karabakh struggle for self-determination, this book captures the essence of the issue with an illuminating portrayal of many of the key figures and events that have come to define the Karabakh issue. The conflict cruelly shaped the destinies of thousands of average people and the ordeals they bore underline the responsibility of those at the top, in whose hands a resolution of the Karabakh conflict rests. The author’s secret, revealed in the pages of Green and Black, is that he does not shy away from presenting those facts and realties no longer considered expedient to remember. Anyone wishing to be informed and regarding the Karabakh conflict must read this book.

Paperback: 416 pages,

Language: English,

2010, Antelias,

ISBN 978-995301816-4.

Watch

https://www.aniarc.am/2018/02/12/hadrut-civilnet-report-12-february-1988/